Read The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War Storyline:

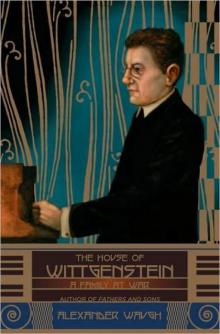

SUMMARY: The modern obsession with celebrity began with the Bright Young People, a voraciously pleasure-seeking band of bohemian party-givers and blue-blooded socialites who romped through the gossip columns of 1920s London. Drawing on the virtuosic and often wrenching writings of the Bright Young People themselves, the biographer and novelist D. J. Taylor has produced an enthralling account of an age of fleeting brilliance. "The laziest way to put someone down is to call him or her an egomaniac. It's what we say when we loathe someone but can't think of anything more precise. That label was often and too easily applied, in London in the late 1920s and early '30s, to members of the so-called Bright Young People: a small, carefully circumscribed circle of elite 20-somethings who seemed to glide, as D. J. Taylor puts it in his nimble new book, on 'a compound of cocktails, jazz, license, abandon and flagrantly improper behavior.' The Bright Young People were the most glamorous, influential, self-absorbed, quasi-bohemian and overeducated creatures in existence. During their flickering moment they were adored and despised in almost equal measure. Good parties are enemy-making machines--You weren't asked? Surely your invitation was lost in the mail--and no one orchestrated them like the Bright Young ones. Nearly every event was an eye-popping spectacle, fully played out in the era's gossip columns. In his novel "Vile Bodies," published in 1930 (and still hilarious), Evelyn Waugh gave an overview of the Champagne-fueled social carnage: 'Masked parties, savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Russian parties, circus parties, parties where one had to dress as somebody else, almost naked parties in St. John's Wood, parties in flats and studios and houses and ships and hotels and nightclubs, in windmills and swimming baths . . . all the succession and repetition of massed humanity. . . . Those vile bodies.' Waugh, of course, was a Bright Young Thing himself, or at the least he existed at the group's margins. So did others who would go on to become well-known artists: John Betjeman, Nancy Mitford, Anthony Powell, Cecil Beaton and Henry Green among them. These bold-face names were among the lucky survivors. More than a few burned out, got lost or threw their promise away. Other would-be Bright Young People, Lytton Strachey snarked, seemed to have 'just a few feathers where brains should be.' Mr. Taylor, the British author of "Bright Young People: The Lost Generation of London's Jazz Age," is a biographer (he has written lives of Thackeray and Orwell) and literary critic, and he tells this story with a good deal of essayistic flair, precision and flyaway wit. Just as important, he relates this ultimately elegiac narrative with a surprising amount of intellectual and emotional sympathy. He plainly wants to be bothered by the Bright Young People's antics, too. 'One of the great consolations of English literary life, ' Mr. Taylor observes, wonderfully, is the idea that 'seriousness is automatically the preserve of people with cheery, proletarian values and prosaic lifestyles--that a barfly with a private income and a web of well-connected friends has already damned himself beyond redemption.'"--Dwight Garner, "The New York Times ""The saga of Beaton, Evelyn Waugh and the less famous social butterflies that everyone called the Bright Young People may be the ideal escapist fantasy for these sober economic times. Theirs was a life of glittering frivolity, of scavenger hunts that stopped traffic in Sloane Square, cocktails and dancing until dawn, notorious gatherings like the Bath and Bottle Party at a swimming pool ('bring a Bath towel and a Bottle' the invitation said), sprees that envious mortals read about in gossip columns. To make the fantasy complete, the story even offers a satisfying touch of schadenfreude. As D. J. Taylor emphasizes in this incisive social history, these flighty creatures crashed with a thud louder than you'd imagine butterflies could make. Taylor compares the Mozart party photo to a 'medieval morality play' capturing how the Bright Young People got their comeuppance: their zaniness became more self-conscious and attenuated; they tried to ignore the fragile postwar economy and the crumbling aristocracy, but those changes were ready to bite them. It was fun while it lasted, though, for much of the 1920s . . . Lightened by the book's beautiful design, laced with mordant period quotations and delicious satiric cartoons from newspapers and magazines. Taylor's richly detailed work also calls attention to two breezy, auspicious first novels about the Bright Young People that are unfortunately out of print: Nancy Mitford's "Highland Fling" and Anthony Powell's "Afternoon Men.""--Caryn James, "The New York Times Book Review" "Combining diaries, biographies, news reports and novels to paint the social life of 1920s London, D.J. Taylor has created that rarest of books--one you can safely recommend both to scholars of Evelyn Waugh and the entourage of Paris Hilton. The engaging "Bright Young People," written by a critic and novelist best known for his biography of George Orwell, reads like a case study in youth culture, trendsetting, log-rolling and cultivated bohemianism. It examines the symbiotic relationship between a loose-knit group of partygoers and a media that, in gossip columns and mocking denunciations, made them the first celebrities who were famous, in our contemporary sense, for being famous. By the most generous estimate, there were never more than 2,000 souls among the ranks popularly known at the time as the Bright Young People. By most accounts, those souls were self-absorbed, self-mythologizing and terribly jaded. Their defining exploits included boisterous scavenger hunts, extravagant hoaxes and the 'stylized debauchery' of more fancy-dress balls than you can shake an engraved 16-inch-high invitation at--including the Bath and Bottle Party, the Circus Party, the Hermaphrodite Party, the Great Urban Dionysia and the Mozart Party, where the menu came from a cookbook owned by Louis XVI. They excited the public imagination--and incited a moderate moral panic--with their fast living and reflexive flippancy. The greatest talents associated with the movement were Waugh and the photographer Cecil Beaton. Taylor deftly traces how the former drew on his friends' exploits for the hysterical satire of "Vile Bodies" and "Decline and Fall," and how the latter--an Edmund Hilary among social climbers--used his to further his career. Lesser accomplishments detailed here include "Singing Out of Tune," a novel by brewery heir Bryan Guinness that documented the Bright Young Person's daily routine: 'waking up late, meeting people for lunch, bringing the lunch party home for tea, moving on to cocktails and dinner . . . and ending up with a communal trek around the fashionable restaurants of the West End.' But in this realm any accomplishment was an exception, and the non-career of the occasional poet Brian Howard proved emblematic of this wasted youth revolt. 'The books Brian Howard never wrote would fill a decent-sized shelf, ' Taylor writes, elsewhere noting that the man lived out his frustrating life 'in that exotic never-never land where the Ritz bar meets the out-of-season Continental resort.' The fun ended soon enough; by 1931, England was in financial crisis and a 10-hour-long Red and White Ball rang down the era. But Taylor's skillful reconstruction of the whole hazy time feels like a lasting party favor."--Troy Patterson, NPR"A poignant study of the elusive relationship between art and the social world from whence it springs . . . D. J. Taylor, author of a first-rate life of George Orwell, shows the sharp instincts of an expert biographer in his approach to a 1920s English youth culture."--Damian Da Costa, "The New York Observer ""In "Bright Young People" Taylor is writing splendid social history, not fiction, and he brings a more tempered and rueful approach, showing the sadness beneath an entire generation's compulsion to waste its promise and dance in the spotlight. Scott Fitzgerald, a writer admired by Waugh (who was no soft touch), called his own 'lost' contemporaries 'the beautiful and damned'; here, Taylor makes us feel the full force of the reckoning implied in that sad conjunction . . . Taylor has a nice way with a one-liner--'The books Brian Howard never wrote would fill a decent-sized shelf'--and is excellent on the evolution of BYP argot . . . By placing generational tensions and tenderness center-stage, Taylor gives his book a beating emotional heart."--Richard Rayner, "Los Angeles"" Times ""Jam-packed and delicious, crammed with a cast of selfish, feckless, darling, talented, almost terminally eccentric, good-looking men and women, "Bright Young People" chronicles the doings of London's gilded youth in the Roaring Twenties. Even if you think you know a lot (or enough) about them; even if you've read the acerbic novels of the early Evelyn Waugh or plowed your way through Anthony Powell's "A Dance to the Music of Time," there's bound to be material here you haven't seen or heard of."--Carolyn See, "The Washington Post ""If the flappers of the 1920s epitomized the Jazz Age on this side of the Atlantic, in England it was the Bright Young People. The British milieu of society scions flinging themselves into the nonstop pursuit of fun in the aftermath of World War I was immortalized--and hilariously flayed--by Evelyn Waugh in 1930 with his novel "Vile Bodies," but the real-life major players who made up this set are long gone. Thanks are due, then, to English critic D.J. Taylor, who brings them back to life in "Bright Young People." Some were distinguished, others once famous only for being famous and now pretty much forgotten--but they were almost invariably fascinating . . . Mr. Taylor also reminds us of lesser-known characters, such as Beverly Nichols and Bryan Guinness, up-and-coming writers whose work fed on this scene and who were celebrated in London at the time . . . "Bright Young People" was published last year in Britain. It arrives on these shores with a new resonance as we contemplate a world in its worst financial straits since the Depression, with many troubling political and military signs on the horizon as well. Then as now, parties everywhere ended as a more sober age dawned."--Martin Rubin, "The Wall Street Journal" " ""Absorbing . . . The book really takes hold when Taylor seizes on the actual trajectory of the lives of individual members, most . . . poignantly that of Elizabeth Ponsonby . . . The pages devoted to her, enriched by Taylor's access to the Ponsonby family papers, are all the biography her lack of accomplishments and frittered-away youth warrant; yet they greatly deepen this study of a social phenomenon."--Katherine A. Powers, "The Boston Globe ""Waugh was at once an enamored occasional participant in the Bright Young People's decadence and a revolted critic of it. In his novels that memorialize the age, "Vile Bodies" especially, the tone Waugh takes toward his generation is ambivalent. In his captivating new history of the age, "Bright Young People: The Lost Generation of London's Jazz Age," D.J. Taylor takes his sense of 1920s London from Waugh: Mr. Taylor's book is at once elegy and critique. And this is just as it should be, because it is hard not to be by turns enthralled by the splendor of this brief age and, in turn, dismayed by its selfishness and frivolity . . . The Bright Young People's decadence, their frivolity, their refusal of moral seriousness for a shared escapist devotion to pleasure is, as it should be--thanks to Mr. Taylor's deft managing of tone--both enticing and repulsive."--Emily Wilkinson, "The Washington Times" "Holroyd is an accomplished accumulator of facts and anecdotes; and he writes easily and fluently."--Richard Jenkyns, "The New Republic" "[Conveys] precisely the aspect of the Bright Young People that is most difficult to give expression to on paper: not books or parties, but 'an atmosphere . . . An outlook, a gesture, an essence.'"--Mark Bostridge, "The Independent on Sunday ""Compelling and ultimately touching . . . A witty and sensitive account of the pathos and the glamour of the generation fated to 'sorrow in sunlight.' "--Rosemary Hill, "The Guardian ""Excellent . . . the brightest of the Bright Young People [make] their fictional counterparts in Waugh pale into insignificance . . . [Taylor] lays bare their cavortings with an archeological eye."--Philip Hoare, "The Independent ""Taylor, for years a journalist, is fascinated by--and authoritative on--the lucrative relationship forged between the shrewdest of the Bright Young People and the glamour-hunting press . . . Shrewd and absorbing in his analysis of the way Waugh and Nancy Mitford . . . promoted the world they would soon skewer in fiction."--Miranda Seymour, "The Sunday Times" (London) "Moving and always entertaining."--Jane Stevenson, "The Daily Telegraph ""Fascinating . . . A complex study of family, fear and breakdown . . . Taylor's achievement is to remind us that there are few periods of recent history more culturally interesting than the years between the wars."--Frances Wilson, "New Statesman ""A goldmine . . . If I had to choose one book as a summing up of the BYP, it would be Taylor's."--Bevis Hillier, "The Spectator ""An engrossing social history of the blue bloods, bohos, and bobos who constituted the 'lost generation' of post-World War I England."--Michael Moynihan, "Wilson Quarterly" "One yearns to have been a fly on the wall at the 'fancy dress ball . . . featuring a gang of fashionable debutantes dressed as the Eton rowing eight, ' or the notorious Bruno Hat exhibition of faked modernist paintings. Taylor expertly connects this shrill game-playing to memorable depictions of it in Waugh's "Vile Bodies," Powell's "Afternoon Men" and Henry Green's "Party Going," while never neglecting the actual achievements of their lesser peers (e.g., Beverley Nichols's forgotten novel "Singing Out of Tune"). A note of genuine pathos is struck in his description of how the increasingly straitened economic and political circumstances of the '30s began rendering this gaudy subculture obsolete. Immensely readable, and of real value as a sharply pointed cautionary tale."--"Kirkus Reviews ""There are . . . plenty of juicy anecdotes to go around . . . The text is enlivened by several "Punch" cartoons from the period, vividly depicting the hold these rich young partygoers once held on the public's imagination."--"Publishers Weekly" SUMMARY: From Alexander Waugh, the author of the acclaimed memoir Fathers and Sons, comes a grand saga of a brilliant and tragic Viennese family.The Wittgenstein family was one of the richest, most talented, and most eccentric in European history. Karl Wittgenstein, who ran away from home as a wayward and rebellious youth, returned to his native Vienna to make a fortune in the iron and steel industries. He bought factories and paintings and palaces, but the domineering and overbearing influence he exerted over his eight children resulted in a generation of siblings fraught by inner antagonisms and nervous tension. Three of his sons committed suicide; Paul, the fourth, became a world-famous concert pianist, using only his left hand and playing compositions commissioned from Ravel and Prokofiev; while Ludwig, the youngest, is now regarded as one of the greatest philosophers of the twentieth century. In this dramatic historical and psychological epic, Alexander Waugh traces the triumphs and vicissitudes of a family held together by a fanatical love of music yet torn apart by money, madness, conflicts of loyalty, and the cataclysmic upheaval of two world wars. Through the bleak despair of a Siberian prison camp and the terror of a Gestapo interrogation room, one courageous and unlikely hero emerges from the rubble of the house of Wittgenstein in the figure of Paul, an extraordinary testament to the indomitable spirit of human survival. Alexander Waugh tells this saga of baroque family unhappiness and perseverance against incredible odds with a novelistic richness to rival Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks.Pages of The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War :